It’s not fake news, it’s very real. This Month in Classical Music History is a series dedicated to finding stories of the good, the bad, and the downright weird. In this article, read about a Beethoven historian who blatantly made things up, the NY Phil’s Young People’s Concerts under Leonard Bernstein, and a scandalous dance scene from an opera that was so seductive, all subsequent performances were cancelled.

January: This Month in Classical Music History

January 16, 1864: Historian Anton Schindler Dies, His Credibility Follows

Little white lies always start off so innocent, don’t they? At first, it’s just one small detail that gets changed. Then, another detail, and another, and more and more until what started off as a harmless fib has spiraled out of control. Anton Felix Schindler must have experienced that thrilling, anxiety-inducing sensation of fibbing as he boasted to others about having the respect and friendship of Ludwig van Beethoven.

Anton Schindler

Schindler was Beethoven’s secretary for three years towards the end of the composer’s life, and after Beethoven’s death, Schindler published a biography on the titanic composer. For a time, the biography was widely accepted. Schindler, after all, was Beethoven’s secretary, so of course he knew a great deal about the composer. Unfortunately for Schindler, scholars detest little white lies – they expect facts.

As it turns out, historians discovered in the 1970s that Schindler falsified a great deal of information about Beethoven after the composer’s death. Evidence proves that Schindler took Beethoven’s conversation books (which he used to communicate once he became deaf) and wrote in conversations that did not happen. Most of these false entries show Beethoven and Schindler having close conversations and mutual displays of respect.

Although Schindler and Beethoven were friends, scholars believe the false entries serve the purpose of elevating Schindler, so that he could enhance his own reputation as a music director. No doubt, it must have been good for Schindler’s career to seem like he was closer than he was with the greatest composer of the era. Schindler’s Biographie von Ludwig van Beethoven still exists today, although scholars would advise reading a more credible source. Too bad, Schindler, looks like you’ve been busted!

January 22, 1907: Strauss Writes Striptease into Opera, Does Not Go Well

Times have certainly changed since the early 1900s regarding what is considered “appropriate” behavior on stage. With modern pop musicians combining dance and covering a broad range of subject matter, today we are relatively unsurprised to hear innuendos of a sexual nature, or even overt declarations of lustful desire.

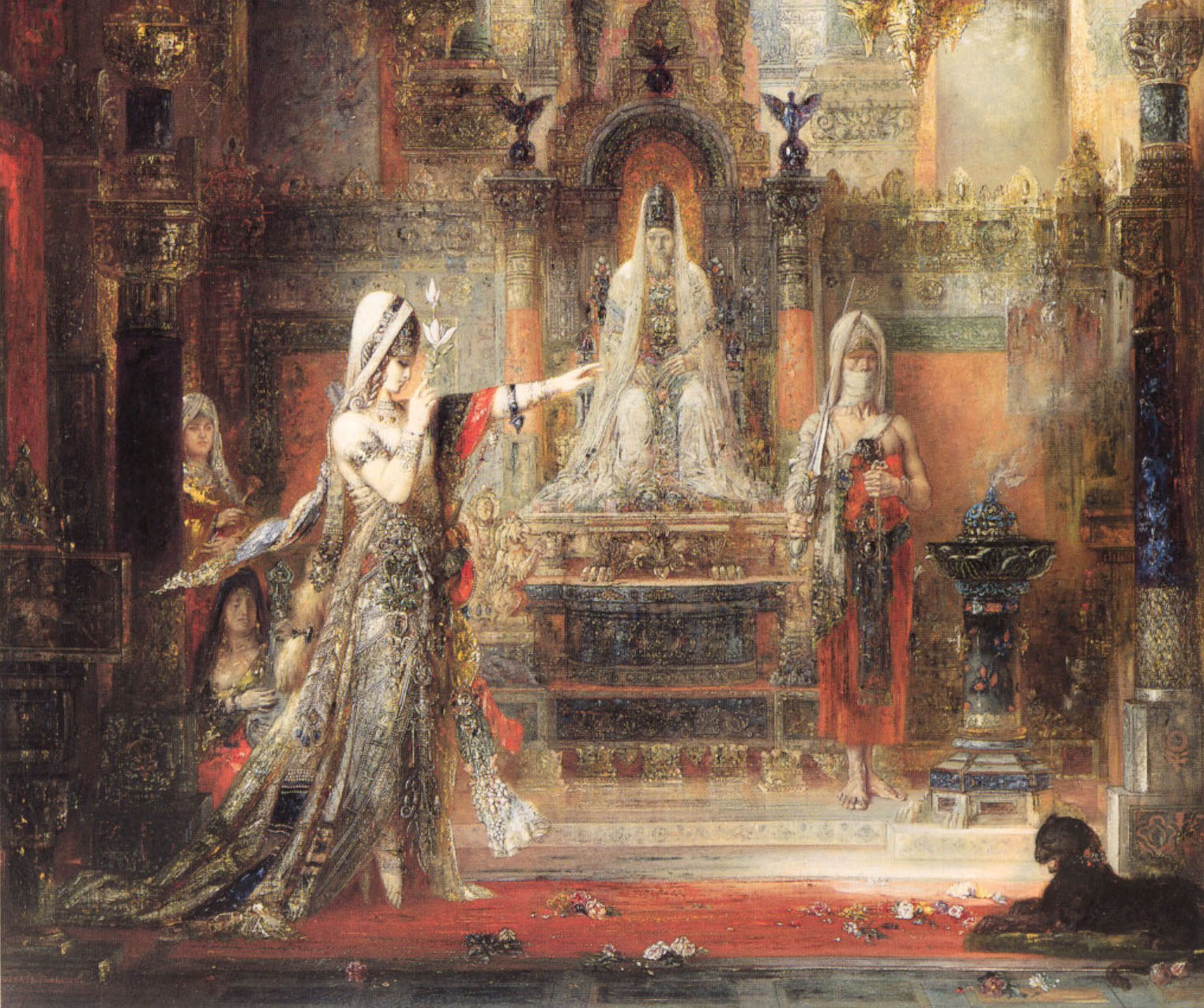

Such was not the case in 1907 for the American premiere of Richard Strauss’ opera Salome. Like many operas, Salome has the essentials: love, murder, drama, and deception. Strauss took things a step farther, though, by including the “Dance of the Seven Veils” in the biblical themed opera, a scene that was so overtly erotic at the time, that the soprano of the original performance, Marie Wittich, refused to do the dance at the premiere. She had a dancer perform in front of her instead, and resumed singing when the dance was finished.

Olive Fremstad holding the head of John the Baptist in the Metropolitan Opera’s 1907 premier of Salome.

Why was the dance so scandalous? Well, it depicts the main character, Salome, slowly and seductively removing her seven veils, one at a time, until she lies naked at the feet of King Herod. She does this because Herod tells her if she dances for him, he will grant her heart’s desire – which she then uses to ask for the head of John the Baptist and then proceeds to kiss the severed head before she is killed off by Herod’s guards.

Even by today’s standards, this is a graphic display. After the US premiere at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City on January 22, 1907, critics were shocked by the nature of this final scene and eventually Strauss was forced to cancel further performances of Salome in America. After a brief period of censorship, the opera was revived in Vienna in 1918, and in the United States in 1934. There are several productions available for viewing on YouTube, (if your curiosity has been piqued, see below!)

January 18, 1958: What Does Music Mean? First Broadcast of Young People’s Concerts

Looney Tunes isn’t the only TV program that broadcast classical music to an entire generation of young minds. The New York Philharmonic’s Young People’s Concerts have been a constant in the American orchestra’s season since 1926. They began as a way to combine lectures about music with musical performances to educate children at the orchestra. Add to this concept the mass production and consumption of television in the 1950s, and the legendary Leonard Bernstein’s creativity, and you’ve got a monumentally successful classical music TV program.

The first broadcast was a concert titled “What Does Music Mean?” that opened with the William Tell Overture by Gioachino Rossini and follows with a great lecture by Bernstein where the conductor tries to answer the question “what does music mean?” According to Bernstein,

Music is never about anything. Music just is. Music is notes, beautiful notes and songs put together in such a way that we get pleasure out of listening to them, that’s all there is to it… The meaning of music is in music… Music has its own meaning right there for you defined inside music itself and you don’t need any stories or any pictures to tell you what it is. If you like music at all, you’ll find out the meaning for yourself, just by listening to it.”

The orchestra goes on to perform Beethoven’s sixth symphony, and Ravel’s La Valse.

The broadcast of the Young People’s Concerts went on for 15 years under the direction of Bernstein, and there are 53 episodes in total. Many of them are available on YouTube for educational purposes, with topics ranging from concertos, jazz, composers, unusual instruments, folk music, and more! The program has been aired in the United States and forty other countries across the globe. Thanks, Lenny and the New York Phil, for inspiring so many youths with the power of music!

Cover image is Salome Dancing before Herod, by Gustave Moreau, 1876.

Someone collected all of Bernstein’s YouTube presentations in one place:

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLi-srbWiDOUQr28PpmahrKmF4X7euOAOi

enjoy

Here’s a sample to start with: “The greatest 5 minutes in music education history”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gt2zubHcER4&t=4s