What is Ecomusicology?

Words by Elizabeth Frickey

The word “ecomusicology” seems relatively straightforward. Just break it down and ecocriticism plus music equals ecomusicology, right? However, there are entire worlds contained within the fields of ecological and environmental studies as well as music or sound studies. Put the two together, and you’ll find not just one ecomusicology but many ecomusicologies creating a wholly dynamic field.

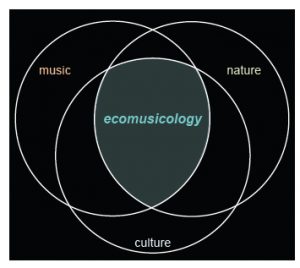

In a very broad sense, as defined by musicologist Aaron S. Allen, ecomusicology is “the study of music, culture, and nature in all the complexities of those terms. Ecomusicology considers musical and sonic issues, both textual and performative, related to ecology and the natural environment.”

Ecomusicology as a field of research is still relatively new, as most major academic writing on the subject has only been done in the last 20 years, but its roots are often traced back to earlier scholarly and artistic efforts. In the 1970s, composer and environmentalist R. Murray Schafer helped to pioneer the field of soundscape studies and acoustic ecology, stressing the interdependency of various fields including acoustics, aural pattern perception, linguistics, and music as equal contributors to the global soundscape.

Ecomusicology is built upon these kinds of interdisciplinary endeavors. Acoustic ecologists, like those represented by the World Forum for Acoustic Ecology, attempt to increase awareness about environmental issues like noise pollution, urban development, and even global warming through artistic and activist approaches. Some scientists and musicians even study non-human sounds, like that of birds or whales, in order to delve deeper into questions of human evolution, musicality, and interspecies music-making.

Of course, ecomusicology has as much to do with the music we already know and love as it does with the sounds we experience outside of music. Composers are often influenced and inspired by their own natural environments and can reference or even mimic these environments using their own musical tools. Take for example well-known nature-inspired works like Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 ‘Pastoral’ or Ralph Vaughan Williams’s The Lark Ascending. Understanding the landscapes that Beethoven and Vaughan Williams might have encountered, whether in Austria or the British countryside, can help us to better understand their music, and vice versa. We may never be able to recreate what an early 19th century rural Austria sounded like with one hundred percent certainty, but thinking ecomusicologically can help us to better understand composers’ relationships to their environment, and ours.

Far from just a passing hot topic in music academia, ecomusicology forces us to reckon with the sounds we hear every day and brings forth major questions, like “what is this thing called music after all?” We are constantly surrounded and deeply affected by sound. A field like ecomusicology that connects sound and music to the world around us is absolutely necessary as we navigate an ever-changing and increasingly noisy world. It reminds and inspires us to look up, to open our ears, and to approach our everyday aural environments with curiosity.

If you’re interested in learning more about ecomusicology, you can read more from Ecomusicology Review, an open access, peer-reviewed journal. For an in-depth conversation on ecomusicology, check out this transcript of a plenary presented by Aaron S. Allen, Jeff Todd Titon, and Denise Von Glahn from 2014 titled “Sustainability and Sound: Ecomusicology Inside and Outside the Academy”.

You can also check out our Ecomusicology playlist on Spotify to do some ecomusicological listening of your own!

Interesting concept and great playlist.