Classical music is rich with history of magnificent music, compelling divas, and innovative composers. Not every world premiere was grand, however. This Month in Classical Music History is a series dedicated to finding stories of the good, the bad, and the downright weird. For November read about Bach serving time in jail, an invention that helped develop the standard tuning pitch of A440 Hz, and an outburst from the New York City Opera stage.

November: This Month in Classical Music History

Bach Goes to Jail, November 6, 1717

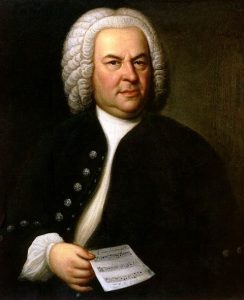

Johann Sebastian Bach.

Johann Sebastian Bach is regarded as an incredibly influential composer, mainly known for his sacred works, but also well-versed in secular Baroque forms. He was a virtuoso organist and a prolific composer. Bach was so good, in fact, that one of his employers threw him in jail upon hearing of Bach’s imminent resignation.

From 1708 to 1717 Bach worked for the Duke of Weimar (in present day Germany) as a court musician. The job began as an organist position for Bach, but gradually evolved with more and more musical responsibilities. Around the time of 1717, the Kapellmeister (Music Director) of the court passed away and Bach wanted to take up the position. Such positions were considered to be the highest rank possible for a musician in the 18th century. He was confident, since he had taken over so many responsibilities, that he would be appointed the new Kapellmeister. When the former Kapellmeister’s son was appointed the position instead, Bach began to seek out other employment opportunities.

Eventually, Bach found potential work in the court of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen. The prince offered to hire Bach as the Kapellmeister of his court, which Bach accepted. When Bach went to turn in his resignation to the Duke of Weimar, the Duke was not pleased, and he imprisoned Bach for a month “for too stubbornly forcing the issue of his dismissal [from the court of the Duke of Weimar]…”

Never one to waste time, Bach simply composed organ exercises during his time in jail. Once he was released, he moved to Köthen and worked there for six years until 1723 when he moved to Leipzig. He lived out the rest of his years in Leipzig, spending time with his family and composing works that so greatly contributed to the Baroque repertoire.

Birth of Johann Scheibler, November 11, 1777

Johann Scheibler.

Sometimes we can take for granted the amount of work that went into developing the common technologies that we use every day. The ‘A’ that every orchestra tunes to at the beginning of a concert, for example, is sounded by the principal oboist, who gets the 440-Hertz pitch from an electronic tuner. But what did people use before electricity? How did people know that they were sounding a pitch at 440 Hz?

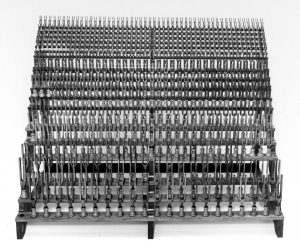

Part of the answer to those questions lies with a man named Johann Scheibler. Scheibler was born on November 11, 1777 and was a silk manufacturer from Prussia. He created a device known as the “tonometer,” an apparatus with 56 tuning forks mounted on wooden planks that determine the frequency of a pitch. The tonometer might seem crude compared to modern electronic tuners, but it played a role in developing a standard method of tuning among musicians. The tonometer had tuning forks that sounded pitches from 220 Hz up to 440 Hz.

Tonometer. Source.

Although tuning forks have been used to tune instruments since the 18th century, having a device that provided a way to mathematically calculate the frequencies of pitch played a role in further understanding the science behind acoustics. In order to calculate frequencies, Scheibler would sound one tuning fork with a known frequency, then sound another with an unknown frequency and count the “beats” per second in between them. In acoustics, beats are the pattern of interference between two sounds (see video below for demonstration). Scheibler’s contribution to the calculation of frequencies paved the way for others to understand how frequencies work with each other – which, in turn, helped musicians by solidifying standards of pitch for tuning their instruments.

Michele Molese Breaks Character on Stage, November 9, 1974

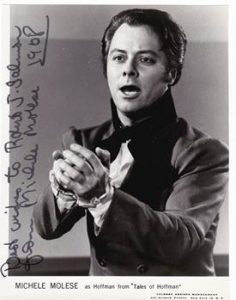

Michele Molese. Source.

The life of an opera star is thrilling and stressful, especially when the performance reviews come around. Michele Molese was an opera tenor in the twentieth century, with an active career from the 50s to the 80s. Molese was born in New York, studied in Milan, and performed in the Netherlands, Italy, and the United States.

In 1974 a music critic by the name of Harold Schonberg wrote a negative review of Molese in The New York Times, chiding the vocalist for singing “squeezed high notes.” Molese was so affected by the review that he broke character at the end of a following performance of Verdi’s “Un Ballo in Maschera” (A Masked Ball). In one of the arias Molese sang a powerful high C, to which the audience reacted with applause. When the applause died down, Molese was reported to have said to the audience “That pinched high C is for Mr. Schonberg!”

Unfortunately for Molese, this outburst led the management of the New York City Opera company to fire him for unprofessional conduct. Molese’s career was not at an end, however. He was able to recover from the incident and went on to perform for many years. The vindication must have felt good to Molese in the moment, but was it really worth losing his job over a jab at Schonberg?

Leave a Reply