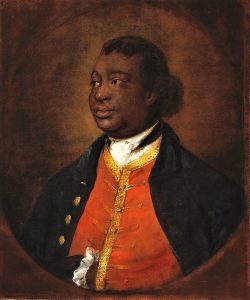

Ignatius Sancho: Composing the Hypocrisy of Colonialism & Convention

Words by Joshua Thompson

Episode 3 from Season 2 of Melanated Moments in Classical Music is sure to go down as one of my favorite episodes of this podcast thus far. I distinctly recall feeling the same way during Season 1 in our feature of Thomas “Blind Tom” Wiggins. The nerdy music sociologist in me cannot help but utilize music from composers of African descent to make world history more digestible and, hopefully, applicable to navigating our global future. Composer, essayist, abolitionist, business owner, and Middle Passage survivor; Ignatius Sancho continues to offer the world of classical music and beyond, poignant, and witty insights into a century’s old philosophical paradigm between the Enlightenment and the hypocritical realities of colonialism and convention indicative of the expanding western empires of the 18th century. In this episode, Angela Brown and I use Sancho’s Minuets Nos. 2 and 10 to go far beyond the music towards a greater understanding of social movements that would eventually disrupt and disturb global commerce, nation-state building and the assumption of white supremacy. As mentioned in this episode, the letters, essays, and correspondences of Ignatius Sancho yield a more personal and substantive illustration of his ideologies than the compositions themselves. The posthumously published Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African (1782) reveal a man who was incredibly devout to the ideals and philosophies of his faith—a faith, it must be noted, that was imposed upon him with his baptism by the Roman Catholic Church, functionally stripping Sancho of any remnants (other than his skin) from his West African culture. While Sancho’s compositions are pure, clean, and refined; his written works are even sharper in their clarity and intention as an abolitionist and philosopher. Sancho holds the mirror to the 18th century idea of Enlightenment and exposes it for what it is: falsely represented and flimsy at best.

“I AM SORRY TO OBSERVE THAT THE PRACTICE OF YOUR COUNTRY, I SAY IT IS WITH RELUCTANCE, THAT I MUST OBSERVE YOUR COUNTRY’S CONDUCT HAS BEEN UNIFORMLY WICKED IN THE EAST, WEST-INDIES, AND EVEN ON THE COAST OF GUINEA… THE ENLIGHTENED CHRISTIAN SHOULD DIFFUSE THE RICHES OF THE GOSPEL OF PEACE WITH THE COMMODITIES OF HIS RESPECTIVE LAND… IN AFRICA, THE POOR… ARE RENDERED SO MUCH THE MORE MISERABLE… THE CHRISTIANS’ ABOMINABLE TRAFFIC FOR SLAVES AND THE HORRID CRUELTY AND TREACHERY OF THE PETTY KINGS ENCOURAGED BY THEIR CHRISTIAN CUSTOMERS… TO FURNISH THEM WITH THE HELLISH MEANS OF KILLING AND KIDNAPPING.”

Ignatius Sancho

Sancho writes most candidly and frequently on these matters with his social contemporaries in Britain. Sancho is well documented mingling with socialites, clergy, novelists, and artists in his mission to expose the immoralities of slavery in Europe and abroad. Much like abolitionism would find its way into the pulpits of the early American church, Sancho leveraged his own community of religious allies, encouraging them to pose abolitionism to their congregations under the framework of God’s divine will for all His creations.

“Consider how great a part of our species–in all ages down to this–have been trod under the feet of cruel and capricious tyrants, who would neither hear their cries, nor pity their distresses. Consider slavery–what it is–how bitter a draught–and how many millions are made to drink it!” I am sure you will applaud me for beseeching you to give one half hour’s attention to slavery, as it is at this day practised in our West Indies. That subject, handled in your striking manner, would ease the yoke (perhaps) of many–but if only of one—Gracious God!–what a feast to a benevolent heart!–and, sure I am, you are an epicurean in acts of charity.–You, who are universally read, and as universally admired–you could not fail–Dear Sir, think in me you behold the uplifted hands of thousands of my brother Moors.” I.S. July, 1776

These letters, nearly 240 years old, coupled with Sancho’s compositions, truly serve as defining cultural markers that chart the course for the next two centuries of racial disparities and inequities sponsored largely in part by religious and nationalistic institutions the world over. Sancho isn’t without his own brand of humor and self-deprecation as he levies stunning indictments against colonial empires. Poking fun at his own obsession with ‘The Divine Philosophy’, he still manages to highlight the complete disconnect between the ideals of Christianity and the behaviors of Christians, once again speaking into the future of the 21st century in the most poignant of ways:

“The man who visits church twice in one day, must either be religious–curious–or idle–which ever you please, my dear friend–turn it the way which best likes you–I will cheerily subscribe to it.–Now I have observed among the modern Saints–who profess to pray without ceasing–that they are so fully taken up with pious meditations–and so wholly absorbed in the love of God–that they have little if any room for the love of man.” I.S. July 27, 1777

It is a wonder Ignatius Sancho was able to maintain even the slightest bit of lightheartedness considering the leading philosophers, thought leaders, and change makers of the time gave no more thought to the creativity and humanity of Black people than they did the assumption of racial superiority squarely in the European’s favor. This is also the ideology that was very much a part of the American Revolution being waged across the pond simultaneously. Philosophers who helped shape the worldview of our founding fathers such as David Hume and Immanuel Kant, were notoriously known for their disregard of the Negro. “I am apt to suspect the Negroes, and in general all the other species of men (for there are four or five different kinds) to be naturally inferior to the whites” (Hume) “[t]he Negroes of Africa have by nature no feeling that rises above the trifling.” (Kant)

And yet, despite their misguided and malicious framing of the Enlightenment, there is overwhelming evidence that Sancho is just one of many Black lives that are the embodiment of the ideals of the time. A prolific contemporary of his time (and one he gives great praise to) was the poet Phyllis Wheatley (1753-1784), the first African living in American to have a book of poems published. Unable to find a single publishing company willing to produce her works in the newly formed United States, Wheatley traveled to London in 1773 and found success there. Ignatius Sancho fully understood the literary and social significance of Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Morals and used the text to further advocate for the end to slavery and the global slave trade amongst his sphere of influence. Ignatius Sancho uses his music as a vehicle to reflect the Divine nature of his Creator which, according to Sancho, is a kingdom greater than any imperialistic endeavor. Sancho is truly a leader of the Enlightenment because his philosophy is always pushing forward and looking upward. He can unapologetically point out the depravity of institutions while offering a glimpse into the future should we choose to embrace the change that is long overdue. “When it shall please the Almighty that things shall take a better turn in America–when the conviction of their madness shall make them court peace–and the same conviction of our cruelty and injustice induce us to settle all points in equity–when that time arrives, my friend, America will be the grand patron of genius–trade and arts will flourish.”

As a composer, Ignatius Sancho positions Baroque and Classical music as a chronological guide to learning world history and the cultures that create it including the entirety of the African diaspora…if you know what you’re listening for.

Links and Resources:

Narrative and Audio of Phyllis Wheatley’s “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral: Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral | Phillis Wheatley | Lit2Go ETC (usf.edu)

Leave a Reply