For our first blog post during Black History Month, we wanted to take a look at a time in American history when the simple act of attending a classical music concert was prohibited for people of color. Renowned African-American opera baritone Robert Honeysucker, who unexpectedly died in 2017, was a student at Tougaloo College in 1963 when he decided to attend a whites-only concert in Jackson, Mississippi. His actions and the many other brave protests of the Civil Rights Movement helped to shed light on the issue of racial prejudice, but how far has classical music really come today?

A Chorus of Opposition After Segregated Concert

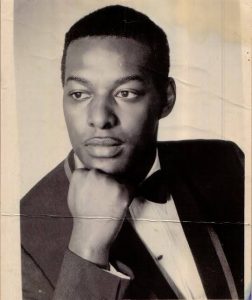

Robert Honeysucker, 1970. Source.

There is a history to the exclusivity of classical music culture in America that can be illustrated by the story of the 1963 arrest of Robert Honeysucker, then a student at Tougaloo College. Racial segregation had not yet been declared unconstitutional, and Jim Crow laws allowed businesses to discriminate against people of color. One such business, the City Auditorium of Jackson, Mississippi, held a whites-only concert on November 1st by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra of England.

Honeysucker and Nicholas Bosanquet, a white British exchange student from Yale, met up to attend the concert, and thus make an anti-segregation statement to the city of Jackson. After presenting their tickets, both Bosanquet and Honeysucker were arrested for trespassing. They were held in jail for a couple of days before being released due to outside pressure from different organizations. The Cambridge Musicians’ Union and the White House applied pressure to Jackson’s local government in the form of threats of investigations to have the charges against the two young men dropped.

In a recent interview about their arrest, Bosanquet remembers the impact their actions had,

the [U.K.] musicians’ union got heavily involved and completely banned appearances at segregated, or exclusively white audiences in the future, so it had a very positive effect, our efforts…it really did lead to a change in attitude of musicians…”

Following this display of courage and the arrest and release of Honeysucker and Bosanquet, students from Tougaloo College began a campaign to put an end to racially segregated concerts. Students wrote letters to nationally known performers who were coming through Jackson, asking them to refuse to perform at whites-only or racially segregated concerts. This led to musicians like Gary Graffman, an internationally acclaimed classical pianist, to refuse to perform in the City Auditorium in Jackson. Other notable performers that refused to perform included Al Hirt, jazz trumpeter, and the cast of the T.V. show Bonanza.

These protests were just one part of the many actions that led to desegregation through the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement. But how far has classical music come? Data from the League of American Orchestras shows only 3% of American orchestral musicians are African-American or Latino.1 In large urban metropolitan areas, where most major orchestras are located, people of color on average make up 48% of the population.2 This means that American orchestras typically do not reflect the broader population of the United States, a discrepancy highlighting that though the civil rights movement ended decades ago, there is much progress still to be made.

Although concerts are no longer racially segregated, the lack of representation of people of color in American classical music is still vast. There are people of color who have persevered and made a place for themselves in classical music, like Robert Honeysucker. But we must remember it was only 55 years ago that Honeysucker was arrested just for trying to attend a concert. It’s up to us today to increase the representation of minorities in our ensembles far beyond 3% so that classical music can have a long future and can be embraced by everyone in our community. To this end, as classical musicians and classical music advocates we need to attend concerts put on by minority musicians, and support organizations that endeavor to make the people on the stage look more like the people in the community. Let’s follow Honeysucker’s example and strive to create a classical music community that is synonymous with inclusivity.

1. http://www.americanorchestras.org/todays_news/604.html

2. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/0504_census_ethnicity_frey.pdf

Cover Photo by Kilyan Sockalingum on Unsplash

Leave a Reply