Contraband Music

Russian music fans of the 1950s and 1960s risked everything to be part of a worldwide music revolution

Words by April Bumgardner. Adapted from Classical Music Indy’s NOTE Magazine.

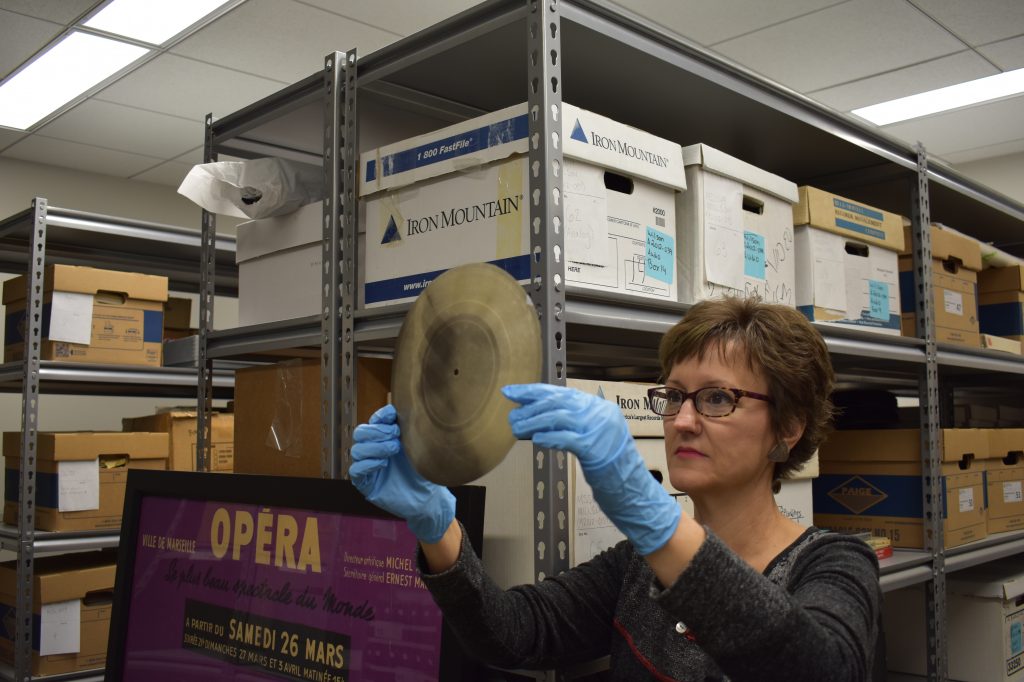

In 2013 Lisa Lobdell, archivist at The Great American Songbook Foundation, received a call that someone had old recordings to donate. “Well, I get this kind of call frequently,” she smiled, “so at first I didn’t think much about it.” Lobdell’s office is nestled upstairs at The Palladium at the Center for the Performing Arts near downtown Carmel where she manages the musical archives and gallery displays. The nature of the donation, however, surprised her. The songs were all recorded on x-ray film.

The donor, Dr. Richard Judy, was a professor of economics and computer science at the University of Toronto until he moved to Indianapolis in 1986 with the Hudson Institute. He is also the founder of TORQWorks, a developer of application software. Back in 1958-1959, however, he was an American graduate student studying political economy in Moscow.

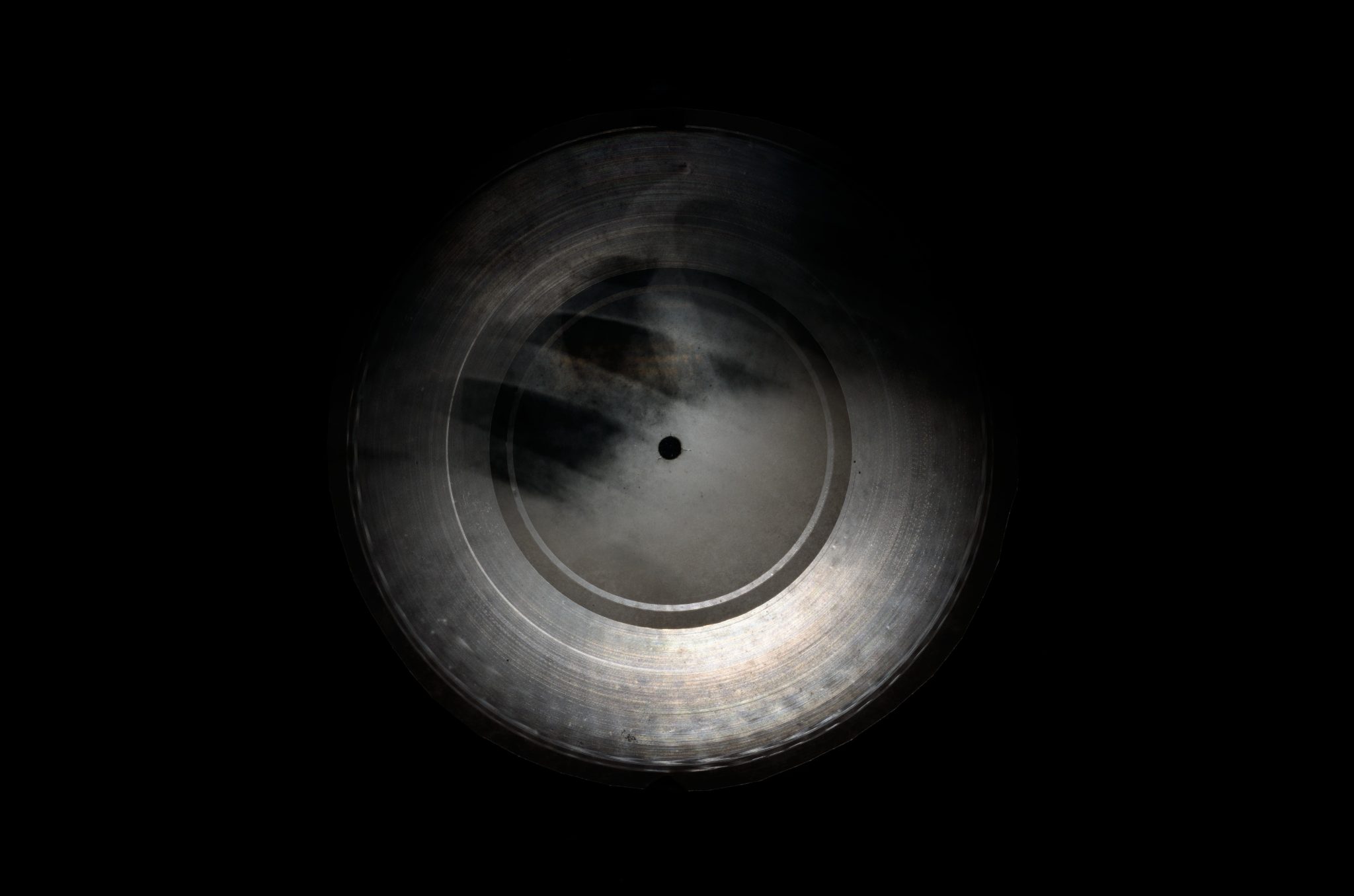

Soon, he discovered a Russian friend was involved in creating bone recordings. Also known as “music on ribs” or “jazz on bones,” these black market recordings were widely circulated during the 1950s and 1960s. Judy eventually returned to the United States with several in his suitcase.

Although the Khrushchev Thaw introduced a lifting of censorship, policies regarding music from the West were still highly regulated. American rock ‘n’ roll and jazz, in particular, were seen as ideologically dangerous. Music enthusiasts found a way around it, however. Thus, the genesis of bone music.

Taking advantage of the vast numbers of discarded x-rays, these opportunists concocted a solution. Fearing the boxes of x-rays would be fire hazards, radiology labs were eager to find ways to dispose of them. Lab technicians jumped at the chance to be rid of the x-ray film when they were offered bottles of vodka in exchange.

Judy’s friend Vitaliy, or “Vit Scrub,” according to a nickname at the time, was the son of a KGB Major General, and was crazy about jazz. “He was very anti-Soviet, though,” says Judy. Vit’s friend, Oleg Kuznetsov, had somehow acquired a German record-cutting machine. Through a painstaking process, Oleg cut the discarded x-rays into discs and recorded to them from bootlegged copies or from live radio play.

Although the Soviets garbled radio programs from the outside, eager music lovers listened to Voice of America in hopes of hearing even a portion of the latest in rock ‘n’ roll or jazz. “There was a great craze for jazz music,” Judy remembers. “My taste ran to classical music, but I had all these jazz records sent over.” An American visitor Judy met by chance in Moscow promised to send several jazz records—a promise he fulfilled after leaving Moscow.

Judy describes Vitaliy and Oleg as businessmen, entrepreneurs and music lovers. “They were building a business in a most unorthodox way,” he says. “To risk being caught, you have to be interested in the technology of making music. You have to have courage, or maybe foolishness, to defy the authorities.”

Because x-ray film was so thin and pliable, they were able to curl stacks of bootlegged copies into small cardboard tubes or discreetly roll them up shirt sleeves. “They would mail them all over the country, to Novosibirsk and God knows where,” Judy recalls. Many were seized and imprisoned. Even so, the cool vibes of jazz began circulating widely. Imagine listening to Elvis, the Stones or Monk, then lifting a flimsy disc to the light and finding a femur or a cranium.

Because x-ray film was so thin and pliable, they were able to curl stacks of bootlegged copies into small cardboard tubes or discreetly roll them up shirt sleeves. “They would mail them all over the country, to Novosibirsk and God knows where,” Judy recalls. Many were seized and imprisoned. Even so, the cool vibes of jazz began circulating widely. Imagine listening to Elvis, the Stones or Monk, then lifting a flimsy disc to the light and finding a femur or a cranium.

Judy’s donations include classics like Rock Around the Clock by Bill Hailey and the Comets, Rocket Boogie by Pete Johnson, an unfortunately-warped We Just Couldn’t Say Goodbye by the Andrews Sisters, and one unknown piece with a peppy Hammond organ, simply labelled “floating rib.”

George Blood of George Blood LP in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania was eager to work with this historic medium. Blood’s digitized archives will soon be available to the public through Indiana University in Bloomington.

If there is a lesson to be learned from this piece of history it is resilience. “People will find ways of doing things,” says Judy. “We have to appreciate the indomitable spirit of human beings to pursue artistic interests in the face of opposition.”

To learn more about The Great American Songbook Foundation, visit their website at thesongbook.org or visit the gallery in person Monday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and Saturday from 12 p.m. to 4 p.m. in the Palladium at 1 Center Green, Carmel, Indiana 46032.

Leave a Reply